Against All Odds

By Christopher Lynch

February 13, 2014

Topanga resident Tony Dow visits some very special artists.

Tony Dow (right) visits with Christian Branscombe, one of the artists privileged to be in one of the “Leisure Time Activity Groups” at the California State Prison in Lancaster, CA. The purpose of these programs is to focus on the positive and, in many cases, to allow the inmates to give back to a society from which they have taken so much.

At first glance it seems like any other art workshop: canvases, in various stages of completion, compete for available wall space, sculptures crowd the workbenches, and wooden easels grip the dreams and visions of the artists that have come here to create. Several of the works proudly display the blue ribbons awarded to them and the pungent smell of oil, acrylic and finishers permeate the air.

Then you notice the tattoos and the powder-blue scrubs with the letters CDCR emblazoned across the back.

Topanga artist Tony Dow visits inmates at the California State Prison, Los Angeles County, located in Lancaster. The select group of inmates are members of the “Progressive Arts program,” one of several L.T.A.G. or “Leisure Time Activity Groups” that exist in the facility. From left, front to back are Aaron Mercado, Joe Silva, Ray Tarazon, Sadiq Salbu, Tony Dow, Jon Grobman, Melvin Lindley, James Heard, Christian Branscombe, Donnell Campbell and John Goemaat.

The concertina wire outside confirms what Dorothy had told Toto: We’re not in Kansas anymore.

Welcome to the California State Prison, Los Angeles County. Located north of Los Angeles in the city of Lancaster, it’s a 262-acre, level-four, maximum-security facility responsible for the housing, clothing and feeding of more than 1,000 inmates.

The high desert is a world away from the wooded landscape of Topanga Canyon, but that didn’t stop sculptor and local resident Tony Dow from visiting the facility recently. He had heard about a very special art program through a friend and wanted to do what he could to support his fellow artists, no matter where they may be.

Dow remarked positively when he visited the facility and saw the program in action: “This is such a better use of energy,” he said emphatically. “As compared to the usual efforts of simply housing them and then using force to try to keep them under control.”

But these are no ordinary inmates and this is no ordinary art program. The artists here are members of the “Progressive Arts program,” one of several L.T.A.G. or “Leisure Time Activity Groups” that exist in the facility. The purpose of these programs is to focus on the positive and, in many cases, to allow the inmates to give back to a society from which they have taken so much.

Chris, an artist and a LWOP— Life Without the Possibility of Parole—explains,

“I know I hurt a lot of people, I made a lot of victims: my friends, my family. And I know that what we’re doing in here cannot balance what we did on the outside, but maybe we can lessen it somewhat.”

All of the art that the inmates create is donated to outside organizations. These organizations then auction it off with the proceeds going to programs such as The Wounded Warrior Project, The American Cancer Society’s Relay for Life and the Blue Star Mothers of America, who use the monies to send care packages to our troops overseas.

Dow’s visit today wasn’t a simple social call, and it wasn’t as routine and prosaic as the hundreds he did in his previous career as a famous child actor; he wasn’t here to simply shake hands and autograph pictures.

These were fellow artists and kindred spirits, and the intense conversations he had with them surrounded technique, materials and the combining of different media. This was, in his words, a chance for him to share and learn.

“I don’t care about talking about my role as Wally on Leave it to Beaver, “he said. “I already know everything about that. But I can talk about art forever, because I can learn something new.”

The inmates donate not just their time, but the materials as well, procurement of which is no easy undertaking.

Jon, another artist who’s been sentenced to 190 years, is the inmate chairman of the program. He says that it can take a minimum of two weeks to get the supplies they need.

“We have to have our family and friends pay for the materials and some of the artists in here just don’t have that ability, so we share a lot of brushes, materials, etc. Even then, it’s a huge bureaucracy to get it through all the security checks. And some stuff we can’t get at all and have to improvise.”

Melvin Lindley, a sculptor who’s doing 17 years to life, describes how he creates his own materials using a combination of bath soap, paper and floor wax. Some of his award-winning work includes a lion, a bouquet of roses and a Dodger figurine.

“I can’t get clay,” he explains. “Because it can dry too hard and the officials are afraid it could be used for a weapon. So I have to make my own raw materials.”

So concerned are the officials that materials could be used in inappropriate ways, the artists had to design their own innovative painting easels – made entirely without hardware such as screws, hinges or bolts. The only exception to the rule is a single drywall screw that is allowed to secure them to the bench.

Entrance into the program is a challenge as well. First of all, the inmates must qualify to be housed at this particular section of the prison, known as “A” yard. The inmates must have a clean record of no incidents for five years and then must sign a contract that states that they will not do drugs, join gangs, or engage in violent behavior. It’s a promise that comes with a heavy price if broken.

Richard, a lifer, and the head of an associated LTAG group called “Veterans Embracing Truth” explains the consequences if they breach their contract.

“In A-Yard we— whites, blacks and Hispanics— all mix freely without fear of reprisal from other inmates. But if I screwed up and broke my contract, I’d be sent back to the other yards, and I’d be killed by one of the gangs over there because I was a white man who got along with a black man.”

Residency in A-Yard still does not guarantee entrance to the art program. Inmates must take several of the art classes that are offered to learn their techniques and build up a substantial portfolio. Then, every three years, the members of the Progressive Arts Program, vote to accept new inmates based upon the quality and quantity of the art produced.

“They have to be producing,” Jon explains. “We need to sustain the program and do good by donating more and more works to the outside. We can’t do that if a guy doesn’t want to produce.”

The average time to produce a new piece per inmate is approximately two weeks.

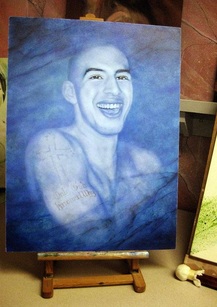

Some of the pieces produced stay much closer to home. Paepole, also known as “Rock,” is another LWOP and the undisputed master artist of the program. He creates special works for other inmates and even prison staff members. In his designated corner near the entrance to the art room sit several paintings that are works in progress. One of them is a blue hued acrylic of a smiling shirtless young man. On the man’s arm is a tattoo that states “Only God Knows Why.” The painting is of the late son of one of the prison staff members. He was in the Army and was killed in combat while serving his country. “Rock” is doing this painting free of charge and for no special privileges. He doesn’t even want to be compensated for his materials. He’s an artist, and this is just what artists do.

Driving back to his home in Topanga Canyon, Tony Dow remarked, “This is an awesome program they have here. Every prison should have a program exactly like this.”

His fellow artists couldn’t agree more.

To view Tony Dow’s many works of art, visit his website at: tonydowsculpture.com.

These were fellow artists and kindred spirits, and the intense conversations he had with them surrounded technique, materials and the combining of different media. This was, in his words, a chance for him to share and learn.

“I don’t care about talking about my role as Wally on Leave it to Beaver, “he said. “I already know everything about that. But I can talk about art forever, because I can learn something new.”

The inmates donate not just their time, but the materials as well, procurement of which is no easy undertaking.

Jon, another artist who’s been sentenced to 190 years, is the inmate chairman of the program. He says that it can take a minimum of two weeks to get the supplies they need.

“We have to have our family and friends pay for the materials and some of the artists in here just don’t have that ability, so we share a lot of brushes, materials, etc. Even then, it’s a huge bureaucracy to get it through all the security checks. And some stuff we can’t get at all and have to improvise.”

Melvin Lindley, a sculptor who’s doing 17 years to life, describes how he creates his own materials using a combination of bath soap, paper and floor wax. Some of his award-winning work includes a lion, a bouquet of roses and a Dodger figurine.

“I can’t get clay,” he explains. “Because it can dry too hard and the officials are afraid it could be used for a weapon. So I have to make my own raw materials.”

So concerned are the officials that materials could be used in inappropriate ways, the artists had to design their own innovative painting easels – made entirely without hardware such as screws, hinges or bolts. The only exception to the rule is a single drywall screw that is allowed to secure them to the bench.

Entrance into the program is a challenge as well. First of all, the inmates must qualify to be housed at this particular section of the prison, known as “A” yard. The inmates must have a clean record of no incidents for five years and then must sign a contract that states that they will not do drugs, join gangs, or engage in violent behavior. It’s a promise that comes with a heavy price if broken.

Richard, a lifer, and the head of an associated LTAG group called “Veterans Embracing Truth” explains the consequences if they breach their contract.

“In A-Yard we— whites, blacks and Hispanics— all mix freely without fear of reprisal from other inmates. But if I screwed up and broke my contract, I’d be sent back to the other yards, and I’d be killed by one of the gangs over there because I was a white man who got along with a black man.”

Residency in A-Yard still does not guarantee entrance to the art program. Inmates must take several of the art classes that are offered to learn their techniques and build up a substantial portfolio. Then, every three years, the members of the Progressive Arts Program, vote to accept new inmates based upon the quality and quantity of the art produced.

“They have to be producing,” Jon explains. “We need to sustain the program and do good by donating more and more works to the outside. We can’t do that if a guy doesn’t want to produce.”

The average time to produce a new piece per inmate is approximately two weeks.

Some of the pieces produced stay much closer to home. Paepole, also known as “Rock,” is another LWOP and the undisputed master artist of the program. He creates special works for other inmates and even prison staff members. In his designated corner near the entrance to the art room sit several paintings that are works in progress. One of them is a blue hued acrylic of a smiling shirtless young man. On the man’s arm is a tattoo that states “Only God Knows Why.” The painting is of the late son of one of the prison staff members. He was in the Army and was killed in combat while serving his country. “Rock” is doing this painting free of charge and for no special privileges. He doesn’t even want to be compensated for his materials. He’s an artist, and this is just what artists do.

Driving back to his home in Topanga Canyon, Tony Dow remarked, “This is an awesome program they have here. Every prison should have a program exactly like this.”

His fellow artists couldn’t agree more.

To view Tony Dow’s many works of art, visit his website at: tonydowsculpture.com.