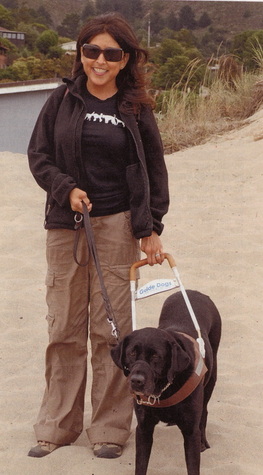

Melissa Hudson and her guide dog Anya

HIGH ACHIEVER: Uveitis and Juvenile Arthritis Couldn’t Keep This Hiker Down

By Christopher J. Lynch

July 1, 2011

Melissa Hudson wept with pride when she stepped onto the summit of Mt. Baldy. She’d lived in the shadow of the 10,000-foot mountain – the highest point in Los Angeles County – all her life, but had never considered climbing it.

“The outdoors was something other people did; it wasn’t for the frail, little girl who lived in constant pain and spent most of her time in doctors’ offices or hospitals,” says Melissa, 37, who was diagnosed with juvenile arthritis (JA) at age 3.

Even more remarkable: Melissa is legally blind due to uveitis, an inflammatory condition associated with JA. And a few years ago, she had to re-learn how to walk after major foot surgery, which was also a byproduct of her JA.

But for Melissa, none of those ailments were going to keep her from accomplishing her goal.

Overcoming Setbacks

In elementary school, Melissa was relegated to an adaptive physical education class because of JA. “In high school, I decided to try to live my life more like everyone else and joined the cheer team. I knew that I would never be able to jump up and do the splits like a regular cheerleader, but I knew that I could do something to participate,” she says.

Although she was able to overcome some of the limitations from JA, her vision was another story. It degraded throughout her teens and early 20s. By the year 2000, at 27, she was declared legally blind and had to quit working as a project manager for a global Internet consulting company.

Melissa wanted relief from the pain, particularly in her feet, and she wanted to be able to accomplish something physical – something outside her comfort zone.

Through the Braille Institute of America, Melissa received mobility training and acquired her guide dog, a black lab named Anya. But then another setback: Her JA symptoms, which had been under control with medicines including prednisone, a biologic and methotrexate, returned. And it made walking almost unbearable.

“Ever since I can remember, my feet were pretty deformed,” Melissa says. “My toes never touched the ground and were crooked and on top of each other. Doctors didn’t think surgery was really needed until 2005, when it got so bad that walking was painful. So they did reconstructive surgery on both feet at the same time.”

After the surgery, Melissa relied on a walker for some time – but the result was worth all the pain and recovery time. “I couldn’t have done that hike without that surgery. It was the first time in my life I could actually feel my toes touching the ground,” she says.

New Heights

Empowered by her repaired feet and a renewed sense of purpose, she joined the Braille Institute’s Baldy for the Blind program. Volunteers from the Los Angeles Meet-up hiking club worked with a select group of blind hikers toward the goal of tackling Mount Baldy. Melissa’s climb was in July 2010.

“When I first joined the program, I gave myself about a 30 percent chance of making it all the way to the top,” Melissa says, “but with each successful training hike, my confidence grew.”

After four months of enduring rugged trails, stream crossings and intense heat, the big morning arrived. Melissa stood with the rest of the hikers and guides at the 6,000-foot elevation trailhead to Mt. Baldy. Between them and the summit were seven miles and 4,000 feet of elevation. It was nearly twice as far and as high as any of them ever had hiked.

“I hadn’t slept well the night before and was extremely nervous when I got up,” Melissa says. “My husband David gave me the best words of encouragement he could have: `Don’t think of it as the big one,’ he said. `Think of it as a training hike for Mount Everest.”‘

Melissa pushed through safely, and eight hours later, stood on the summit with her fellow hikers. It was one of the proudest moments of Melissa’s life. The little pain-wracked girl that couldn’t, now could.

“Now, any time I’m feeling a little low, I just think of that moment and of what I accomplished,” Melissa says. “Four little words – `I can’t do this’ – no longer exist in my vocabulary.”

A documentary film is being produced of the adventure. You can view a trailer and see Melissa and her fellow hikers at: www.baldyfortheblind.com

By Christopher J. Lynch

July 1, 2011

Melissa Hudson wept with pride when she stepped onto the summit of Mt. Baldy. She’d lived in the shadow of the 10,000-foot mountain – the highest point in Los Angeles County – all her life, but had never considered climbing it.

“The outdoors was something other people did; it wasn’t for the frail, little girl who lived in constant pain and spent most of her time in doctors’ offices or hospitals,” says Melissa, 37, who was diagnosed with juvenile arthritis (JA) at age 3.

Even more remarkable: Melissa is legally blind due to uveitis, an inflammatory condition associated with JA. And a few years ago, she had to re-learn how to walk after major foot surgery, which was also a byproduct of her JA.

But for Melissa, none of those ailments were going to keep her from accomplishing her goal.

Overcoming Setbacks

In elementary school, Melissa was relegated to an adaptive physical education class because of JA. “In high school, I decided to try to live my life more like everyone else and joined the cheer team. I knew that I would never be able to jump up and do the splits like a regular cheerleader, but I knew that I could do something to participate,” she says.

Although she was able to overcome some of the limitations from JA, her vision was another story. It degraded throughout her teens and early 20s. By the year 2000, at 27, she was declared legally blind and had to quit working as a project manager for a global Internet consulting company.

Melissa wanted relief from the pain, particularly in her feet, and she wanted to be able to accomplish something physical – something outside her comfort zone.

Through the Braille Institute of America, Melissa received mobility training and acquired her guide dog, a black lab named Anya. But then another setback: Her JA symptoms, which had been under control with medicines including prednisone, a biologic and methotrexate, returned. And it made walking almost unbearable.

“Ever since I can remember, my feet were pretty deformed,” Melissa says. “My toes never touched the ground and were crooked and on top of each other. Doctors didn’t think surgery was really needed until 2005, when it got so bad that walking was painful. So they did reconstructive surgery on both feet at the same time.”

After the surgery, Melissa relied on a walker for some time – but the result was worth all the pain and recovery time. “I couldn’t have done that hike without that surgery. It was the first time in my life I could actually feel my toes touching the ground,” she says.

New Heights

Empowered by her repaired feet and a renewed sense of purpose, she joined the Braille Institute’s Baldy for the Blind program. Volunteers from the Los Angeles Meet-up hiking club worked with a select group of blind hikers toward the goal of tackling Mount Baldy. Melissa’s climb was in July 2010.

“When I first joined the program, I gave myself about a 30 percent chance of making it all the way to the top,” Melissa says, “but with each successful training hike, my confidence grew.”

After four months of enduring rugged trails, stream crossings and intense heat, the big morning arrived. Melissa stood with the rest of the hikers and guides at the 6,000-foot elevation trailhead to Mt. Baldy. Between them and the summit were seven miles and 4,000 feet of elevation. It was nearly twice as far and as high as any of them ever had hiked.

“I hadn’t slept well the night before and was extremely nervous when I got up,” Melissa says. “My husband David gave me the best words of encouragement he could have: `Don’t think of it as the big one,’ he said. `Think of it as a training hike for Mount Everest.”‘

Melissa pushed through safely, and eight hours later, stood on the summit with her fellow hikers. It was one of the proudest moments of Melissa’s life. The little pain-wracked girl that couldn’t, now could.

“Now, any time I’m feeling a little low, I just think of that moment and of what I accomplished,” Melissa says. “Four little words – `I can’t do this’ – no longer exist in my vocabulary.”

A documentary film is being produced of the adventure. You can view a trailer and see Melissa and her fellow hikers at: www.baldyfortheblind.com