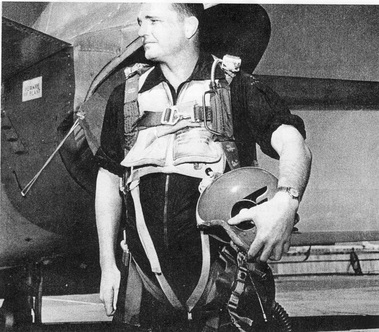

George Franklin Smith before that fateful day

Ejection At

Mach 1.05

By Christopher J. Lynch

October 3, 2008

In 1955 a Manhattan Beach test pilot ejected from his F-100 Super

Sabre just off the coast while traveling faster than the speed of sound. His survival helped astonished scientists design equipment that would enable future pilots to survive Mach 1 ejections

Many of us know that Edwards Air Force base (formerly Muroc Army Airfield) is where Chuck Yeager became the first pilot to break the sound barrier. And that Cape Canaveral, Florida is the launching pad of America’s many forays into outer space. And that Houston, Texas is the home of the Johnson Space Center, where Hollywood – erroneously – told us that Apollo astronaut Jim Lovell made that fateful comment: “Houston; We have a problem.” (It was actually Jack Swigart who said, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”)

But how many of us know that just a few miles off of the South Bay Coast, another aviation first occurred? In 1955, Manhattan Beach resident George Franklin Smith became the first pilot to eject from a jet traveling at supersonic speed…and live!

Fate And A Love Of Flying

Jet aviation was in its heyday. Yeager had broken the sound barrier just eight years previous in October 1947, with the Russians following close behind in December 1948. The space age had not officially begun, but a race in the skies overhead was at full throttle. With the cold war raging and air superiority a pre-requisite for victory, planes were being pushed to their limits. The stick and rudder jockeys steering these fantastic machines into the record books had a one in four mortality rate.

George Franklin Smith was a thirty-one year old bachelor and veteran test pilot for North American Aviation – the forerunner of Rockwell Aviation.

On February 26, 1955, a Saturday, Smith left his small apartment at 2214 Manhattan Avenue intending to run some errands (His apartment building has since been razed. J On a whim, he steered his old Mercury northward and headed towards the North American plant at 2214 Manhattan Avenue intending to run some errands (his apartment building has since been razed). On a whim, he steered his old Mercury northward and headed towards the North American Aviation plant at LAX. He had some flight reports to catch up on and wated to get them out of the way so that he could have the rest of the weekend to relax. He completed the paperwork and was ready to leave for the day when flight dispatcher Bob Gallahue asked him if to flight test a new F-100 jet fighter so that it could be delivered to the Air Force.

Never one to turn down an opportunity to fly, he readily agreed and was soon on his way to the flight line and into aviation’s record books. Smith was so anxious to get into the cockpit that he didn’t bother suiting up in the reinforced nylon suit and sturdy boots normally required for flight, opting instead to simply put his life-vest and parachute directly over his slacks and sport shirt.

The F-100 “Hun” Super Sabre

North American had introduced the F• 100 to the Air Force in 1953 as a daytime supersonic fighter. The aircraft’s performance was exceptional. However, control of the aircraft at high speed hovered on the edge of the envelope. It had a reputation for instability as well as structural and hydraulic failures. One North American test pilot, George Welch, had already been killed in an F-100, and an entire fleet of planes at nearby George Air Force base in Victorville, California had been grounded after a string of major accidents. The grounding had ended just months before Smith climbed into the cockpit of plane number 659.

While going through the instrument and sys-tem checks Smith noticed a stiffer than usual fore and aft stick movement. This was the con-trol that brought the plane’s nose up and down. He thought it might be his imagination, but ran through a simple hydraulic test just the same. When the test failed to reveal any defects, he fired up the big Pratt and Whitney jet engine. The weather was cloudy and cool that day and a slight rain would threaten, but none of this mattered to Smith as he lifted off from LAX. With after-burners ablaze, he rapid-ly climbed through the 8,000 ft. cloud cover that blanketed Los Angeles.

After circling around the Palos Verdes Peninsula, he headed south on his usual course towards San Diego and climbed to a cruising altitude of approximately 35,000 ft. The plane was nearly at super-sonic speed over the waters off of Laguna Beach when the dreaded Mr. Murphy reared hi ugly head.

“Controls locked – I’m going straight in!”Just as the plane was about to break the sound barrier – the point known as “transonic” – it began to nose over and head slightly downward. This was a normal phenomenon for crossing into supersonic speed and a pilot typically had to “re-trim,” or pull back on the controls, to bring the aircraft back to level flight. Smith pulled back on the stick and nothing happened. The stick would not budge. He pulled harder and the plane continued to nose down, its angle of attack increasing rapidly to 20 degrees. He radioed the company radio sta-tion that he was having hydraulic problems. The plane continued to pitch over.

He grabbed the stick with both hands and pulled with all of the strength his 215 lbs. frame could muster. The plane continued to dive. He was now at 80 degrees and feeling himself come off of the seat from negative G’s. He was in an uncontrolled dive heading straight into the Pacific Ocean.

George Kinkella, another F-100 test pilot flying in the area, heard Smith’s desperate radio transmission and saw the vertical contrail heading towards the ocean. Kinkella screamed to Smith over the radio to bail out. Smith need-ed no further coaxing and hastily made the preparations to eject from his stricken craft. As the altimeter spun madly in front of him, he shut down the plane’s engine, set the speed brake, and pulled the helmet visor over his eyes. Then he pulled up on the right armrest that blew the plane’s canopy off. The next sound was indescribable.

The rush of the outside air at 777 miles per hour filled the F-100′s cockpit like a perpetual explosion. A normally fearless man, George instinctively hunched over into a fetal position – exactly the wrong position to be in for ejection. He doesn’t remember pulling the trigger to launch the seat, but he remembers seeing the mach-meter just before he sent himself rocketing out. It read mach 1.05. His exposed body would be travelling faster than the speed of sound!

Seat Ejection: E+0-2 SECONDS

Ejection from an aircraft under normal conditions (level flight, sub-sonic speedy is dangerous. A pilot’s body is first subjected to the G- forces of the rocket engines that fire to move the seat out of the cockpit and away from the plane. This is followed by an explosive charge that essentially blows the pilot out of his seat so that the parachute can open safely. Many pilots who eject suffer career ending injuries.

In the first few seconds of ejection Smith decelerated rapidly due to the poor aerodynamic of his seat. This is known as ‘negative G’s” and has the effect of causing blood and organs to continue in the direction of travel while the body tries to contain them. It has been estimated that Smith’s body endured 40 Gs of deceleration forces. This would have the effect of increasing the relative weight of his body to 8,000 pounds. Blood rushed forward and seated countless bruises over his body. His eyeballs literally tried to pop out of their sockets and intense hemorrhages turned the whites of his eyes to crim-son red His internal organs were thrown against the cavity walls so forcefully that his intestines were lodged against his pelvis and surgery was later required to repair them. The concusssive force of the air pressure caused blood to pour from his ears. Then the seat charge went off and his exposed body blew into the still violent brick-wall of air.

Seat Separation:E+ 2.4 SECONDS

Separated from his seat now, the air created a chaotic turbulence that ripped his clothes to shreds, tore off his shoes and socks and threw his body about crazily. His helmet and oxygen mask were torn from his head. His body pin-wheeled so forcefully that his tight fitting flight gloves, his watch, and even his ring were centrifuged from his hands. By now he was unconscious and his body was rapidly going into shock. When his parachute opened automatically roughly a third of the canopy was torn away.

Luck

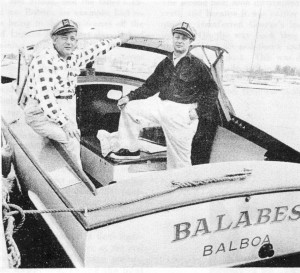

For all of the bad things that happened that day, Smith’s luck was about to turn. Just below him in the water were two fishermen, Art Berkell and Mel Simon. They had motored out into the waters off of Laguna in Simon’s 20- foot cruiser “Balabes”.

Smith’s abandoned F-100 hit the water only 200 yards away from the Balabes, causing the small boat to nearly leap out of the water. Hearing the exploding sound of the supersonic craft hitting the water and seeing the huge geyser of white foam that followed, the two men feared they had somehow drifted into a navel firing range.

They started the boat’s engines and were just about to beat a hasty retreat out of the area when they noticed a limp figure hanging from a parachute. They spun their craft around and raced toward him.

Just as George Smith’s unconscious body touched the water, the second stroke of good fortune came to bear on the flyer. Although it had been calm that day, a slight puff of a breeze caught what remained of the parachute canopy and held it inflated. This, and the air in the slight bit of clothing that remained on the pilot’s body, kept him afloat. Automatically inflating life jackets had yet to be invented, and Smith would have sunk beneath the water in a matter of seconds had this puff of air not materialized

In just under a minute, Berkell and Simon reached Smith. Again, luck played a rote as Berkell had been a former navel air-sea rescue man and took control of the situation. The two hauled Smith’s limp body into the boat and immediately began motoring for shore. Kinkella in his F-100 and another Super Sabre pilot circled overhead. At this point a final element of luck played out far the nearly dead pilot. A Coast Guard Auxiliary cruiser was in the area performing rescue and first-aid operations that day and they too had seen the plane hit the water and Smith’s body floating down. The cruiser intercepted the Balabes and Smith was quickly transferred to the Coast Guard vessel.

When the Coast Guard cruiser reached port in Newport Harbor, an ambulance was waiting to rush the nearly dead pilot to Hoag Memorial Hospital. Smith barely had a pulse and was in a coma. No one – including the Air Force’s own aviation doctors who were rushing to the scene – had any experience with such a situation. Previous knowledge of the trauma inflicted on a body from such extreme G•forces was limited to autopsies performed on people who had fallen from great heights.

A few miles from where his plane crashed into the Pacific, Pearl Phillipson had been instructing her fifth grade class at Aliso Elementary School in South Laguna Beach. The sonic boom created when Smith’s Super Sabre hit the water rattled the windows in the school, as well as the students and Phillipson’s nerves. After reading about the crash in the newspaper several days later, she asked her class to pen essays expressing their thoughts and feelings about the pilot. A nurse read the essays to the comatose pilot. When Smith finally regained consciousness five days later, on Thursday, March 3, it was to the sounds of those heartfelt words written to him by the young students. The disoriented and nearly blind pilot later described these letters as the best medicine anyone could have given him.

Lessons For Future Pilots

During his nearly half-year convalescence, Smith was the subject of intense scrutiny by scientists in medical aviation. He was poked and prodded nearly every which way from Sunday. His experience was the catalyst for redesigning helmets as well as ejection seats. The push to design self-inflating life jackets gained renewed interest. The most important contribution in many pilots’ eyes, however, was the fact that George Smith had proved a pilot could survive a supersonic ejection. How many pilots from this point on would eject – and survive – rather than try to pull it out and auger in, could only be guessed.

Smith died of natural causes at the age of 75 on May 1, 1999 in Orange County.

Mach 1.05

By Christopher J. Lynch

October 3, 2008

In 1955 a Manhattan Beach test pilot ejected from his F-100 Super

Sabre just off the coast while traveling faster than the speed of sound. His survival helped astonished scientists design equipment that would enable future pilots to survive Mach 1 ejections

Many of us know that Edwards Air Force base (formerly Muroc Army Airfield) is where Chuck Yeager became the first pilot to break the sound barrier. And that Cape Canaveral, Florida is the launching pad of America’s many forays into outer space. And that Houston, Texas is the home of the Johnson Space Center, where Hollywood – erroneously – told us that Apollo astronaut Jim Lovell made that fateful comment: “Houston; We have a problem.” (It was actually Jack Swigart who said, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”)

But how many of us know that just a few miles off of the South Bay Coast, another aviation first occurred? In 1955, Manhattan Beach resident George Franklin Smith became the first pilot to eject from a jet traveling at supersonic speed…and live!

Fate And A Love Of Flying

Jet aviation was in its heyday. Yeager had broken the sound barrier just eight years previous in October 1947, with the Russians following close behind in December 1948. The space age had not officially begun, but a race in the skies overhead was at full throttle. With the cold war raging and air superiority a pre-requisite for victory, planes were being pushed to their limits. The stick and rudder jockeys steering these fantastic machines into the record books had a one in four mortality rate.

George Franklin Smith was a thirty-one year old bachelor and veteran test pilot for North American Aviation – the forerunner of Rockwell Aviation.

On February 26, 1955, a Saturday, Smith left his small apartment at 2214 Manhattan Avenue intending to run some errands (His apartment building has since been razed. J On a whim, he steered his old Mercury northward and headed towards the North American plant at 2214 Manhattan Avenue intending to run some errands (his apartment building has since been razed). On a whim, he steered his old Mercury northward and headed towards the North American Aviation plant at LAX. He had some flight reports to catch up on and wated to get them out of the way so that he could have the rest of the weekend to relax. He completed the paperwork and was ready to leave for the day when flight dispatcher Bob Gallahue asked him if to flight test a new F-100 jet fighter so that it could be delivered to the Air Force.

Never one to turn down an opportunity to fly, he readily agreed and was soon on his way to the flight line and into aviation’s record books. Smith was so anxious to get into the cockpit that he didn’t bother suiting up in the reinforced nylon suit and sturdy boots normally required for flight, opting instead to simply put his life-vest and parachute directly over his slacks and sport shirt.

The F-100 “Hun” Super Sabre

North American had introduced the F• 100 to the Air Force in 1953 as a daytime supersonic fighter. The aircraft’s performance was exceptional. However, control of the aircraft at high speed hovered on the edge of the envelope. It had a reputation for instability as well as structural and hydraulic failures. One North American test pilot, George Welch, had already been killed in an F-100, and an entire fleet of planes at nearby George Air Force base in Victorville, California had been grounded after a string of major accidents. The grounding had ended just months before Smith climbed into the cockpit of plane number 659.

While going through the instrument and sys-tem checks Smith noticed a stiffer than usual fore and aft stick movement. This was the con-trol that brought the plane’s nose up and down. He thought it might be his imagination, but ran through a simple hydraulic test just the same. When the test failed to reveal any defects, he fired up the big Pratt and Whitney jet engine. The weather was cloudy and cool that day and a slight rain would threaten, but none of this mattered to Smith as he lifted off from LAX. With after-burners ablaze, he rapid-ly climbed through the 8,000 ft. cloud cover that blanketed Los Angeles.

After circling around the Palos Verdes Peninsula, he headed south on his usual course towards San Diego and climbed to a cruising altitude of approximately 35,000 ft. The plane was nearly at super-sonic speed over the waters off of Laguna Beach when the dreaded Mr. Murphy reared hi ugly head.

“Controls locked – I’m going straight in!”Just as the plane was about to break the sound barrier – the point known as “transonic” – it began to nose over and head slightly downward. This was a normal phenomenon for crossing into supersonic speed and a pilot typically had to “re-trim,” or pull back on the controls, to bring the aircraft back to level flight. Smith pulled back on the stick and nothing happened. The stick would not budge. He pulled harder and the plane continued to nose down, its angle of attack increasing rapidly to 20 degrees. He radioed the company radio sta-tion that he was having hydraulic problems. The plane continued to pitch over.

He grabbed the stick with both hands and pulled with all of the strength his 215 lbs. frame could muster. The plane continued to dive. He was now at 80 degrees and feeling himself come off of the seat from negative G’s. He was in an uncontrolled dive heading straight into the Pacific Ocean.

George Kinkella, another F-100 test pilot flying in the area, heard Smith’s desperate radio transmission and saw the vertical contrail heading towards the ocean. Kinkella screamed to Smith over the radio to bail out. Smith need-ed no further coaxing and hastily made the preparations to eject from his stricken craft. As the altimeter spun madly in front of him, he shut down the plane’s engine, set the speed brake, and pulled the helmet visor over his eyes. Then he pulled up on the right armrest that blew the plane’s canopy off. The next sound was indescribable.

The rush of the outside air at 777 miles per hour filled the F-100′s cockpit like a perpetual explosion. A normally fearless man, George instinctively hunched over into a fetal position – exactly the wrong position to be in for ejection. He doesn’t remember pulling the trigger to launch the seat, but he remembers seeing the mach-meter just before he sent himself rocketing out. It read mach 1.05. His exposed body would be travelling faster than the speed of sound!

Seat Ejection: E+0-2 SECONDS

Ejection from an aircraft under normal conditions (level flight, sub-sonic speedy is dangerous. A pilot’s body is first subjected to the G- forces of the rocket engines that fire to move the seat out of the cockpit and away from the plane. This is followed by an explosive charge that essentially blows the pilot out of his seat so that the parachute can open safely. Many pilots who eject suffer career ending injuries.

In the first few seconds of ejection Smith decelerated rapidly due to the poor aerodynamic of his seat. This is known as ‘negative G’s” and has the effect of causing blood and organs to continue in the direction of travel while the body tries to contain them. It has been estimated that Smith’s body endured 40 Gs of deceleration forces. This would have the effect of increasing the relative weight of his body to 8,000 pounds. Blood rushed forward and seated countless bruises over his body. His eyeballs literally tried to pop out of their sockets and intense hemorrhages turned the whites of his eyes to crim-son red His internal organs were thrown against the cavity walls so forcefully that his intestines were lodged against his pelvis and surgery was later required to repair them. The concusssive force of the air pressure caused blood to pour from his ears. Then the seat charge went off and his exposed body blew into the still violent brick-wall of air.

Seat Separation:E+ 2.4 SECONDS

Separated from his seat now, the air created a chaotic turbulence that ripped his clothes to shreds, tore off his shoes and socks and threw his body about crazily. His helmet and oxygen mask were torn from his head. His body pin-wheeled so forcefully that his tight fitting flight gloves, his watch, and even his ring were centrifuged from his hands. By now he was unconscious and his body was rapidly going into shock. When his parachute opened automatically roughly a third of the canopy was torn away.

Luck

For all of the bad things that happened that day, Smith’s luck was about to turn. Just below him in the water were two fishermen, Art Berkell and Mel Simon. They had motored out into the waters off of Laguna in Simon’s 20- foot cruiser “Balabes”.

Smith’s abandoned F-100 hit the water only 200 yards away from the Balabes, causing the small boat to nearly leap out of the water. Hearing the exploding sound of the supersonic craft hitting the water and seeing the huge geyser of white foam that followed, the two men feared they had somehow drifted into a navel firing range.

They started the boat’s engines and were just about to beat a hasty retreat out of the area when they noticed a limp figure hanging from a parachute. They spun their craft around and raced toward him.

Just as George Smith’s unconscious body touched the water, the second stroke of good fortune came to bear on the flyer. Although it had been calm that day, a slight puff of a breeze caught what remained of the parachute canopy and held it inflated. This, and the air in the slight bit of clothing that remained on the pilot’s body, kept him afloat. Automatically inflating life jackets had yet to be invented, and Smith would have sunk beneath the water in a matter of seconds had this puff of air not materialized

In just under a minute, Berkell and Simon reached Smith. Again, luck played a rote as Berkell had been a former navel air-sea rescue man and took control of the situation. The two hauled Smith’s limp body into the boat and immediately began motoring for shore. Kinkella in his F-100 and another Super Sabre pilot circled overhead. At this point a final element of luck played out far the nearly dead pilot. A Coast Guard Auxiliary cruiser was in the area performing rescue and first-aid operations that day and they too had seen the plane hit the water and Smith’s body floating down. The cruiser intercepted the Balabes and Smith was quickly transferred to the Coast Guard vessel.

When the Coast Guard cruiser reached port in Newport Harbor, an ambulance was waiting to rush the nearly dead pilot to Hoag Memorial Hospital. Smith barely had a pulse and was in a coma. No one – including the Air Force’s own aviation doctors who were rushing to the scene – had any experience with such a situation. Previous knowledge of the trauma inflicted on a body from such extreme G•forces was limited to autopsies performed on people who had fallen from great heights.

A few miles from where his plane crashed into the Pacific, Pearl Phillipson had been instructing her fifth grade class at Aliso Elementary School in South Laguna Beach. The sonic boom created when Smith’s Super Sabre hit the water rattled the windows in the school, as well as the students and Phillipson’s nerves. After reading about the crash in the newspaper several days later, she asked her class to pen essays expressing their thoughts and feelings about the pilot. A nurse read the essays to the comatose pilot. When Smith finally regained consciousness five days later, on Thursday, March 3, it was to the sounds of those heartfelt words written to him by the young students. The disoriented and nearly blind pilot later described these letters as the best medicine anyone could have given him.

Lessons For Future Pilots

During his nearly half-year convalescence, Smith was the subject of intense scrutiny by scientists in medical aviation. He was poked and prodded nearly every which way from Sunday. His experience was the catalyst for redesigning helmets as well as ejection seats. The push to design self-inflating life jackets gained renewed interest. The most important contribution in many pilots’ eyes, however, was the fact that George Smith had proved a pilot could survive a supersonic ejection. How many pilots from this point on would eject – and survive – rather than try to pull it out and auger in, could only be guessed.

Smith died of natural causes at the age of 75 on May 1, 1999 in Orange County.